Editor's Note:

2025 marks the 80th anniversary of the victory of the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union, and the World Anti-Fascist War, as well as the 80th anniversary of the founding of the United Nations. At this important historical juncture, to commemorate the great victory of the World Anti-Fascist War, prevent the resurgence of new fascism, address the complex challenges faced by the Global South amidst multipolarity, deglobalization, and the rise of new fascism, and effectively strengthen solidarity, exchange, and cooperation among Global South nations in the common pursuit and defense of a fair and just post-war world order centered on the United Nations, the "Global South Academic Forum (2025)" will be held in Shanghai on November 13-14, 2025. The theme of this forum is "The Victory of the World Anti-Fascist War and the Postwar International Order: Past and Future."

The Global South Academic Forum has partnered with Guancha to run the "Voices of the Global South" column, featuring articles by guests collaborating with the forum. Mr. Lin Boyao, the interviewee in this article, will attend the "Global South Academic Forum (2025)" as a speaker.

September 30th is the National Memorial Day for Martyrs established by the state. Eighty years ago, after 14 years of bloody battle, the Chinese people completely defeated the Japanese militarist aggressors, proclaiming the total victory of the World Anti-Fascist War. This victory was a historical turning point for the Chinese nation, leading it from a profound modern crisis towards great rejuvenation, and it also marked a major turning point in global development. Today, we commemorate the victory not only to remember history but also to look forward to the future.

"Perpetrator nations and perpetrator states should reflect on the past, admit their errors, apologize or offer compensation to Asian victims, and guarantee that such incidents will never happen again. At the same time, victimized nations and victimized states also have a historical obligation to express the pain, suffering, anger, and even hatred brought upon them by imperialism and militarism; without this expression, the perpetrator nations will never understand."

This statement comes from Lin Boyao, an 86-year-old overseas Chinese residing in Japan, who previously served as a council member of the China Overseas Friendship Association and Secretary-General of the Overseas Chinese Association for the Promotion of Sino-Japanese Friendship and Exchange in Japan. He recently held an online conversation with Guancha.

Lin Boyao's family history can be seen as a microcosm of modern Sino-Japanese and East Asian history. In 1913, his father, Lin Tonglu (1892-1977), traveled from Fuqing, Fujian, to Japan to make a living; his mother, Yang Jinsong (1906-1962), was born in Busan and married his father in Japan in 1922. Lin Boyao was born in Kyoto, Japan, in 1939, making him a Chinese person born and raised in Japan. Due to this unique family background, his life has been deeply entangled in the tumultuous relationship between China and Japan.

After graduating from the Faculty of Engineering at Kyoto University, Japan, in 1964, Lin Boyao began his career and frequently participated in overseas Chinese youth movements. As early as the 1970s, he advocated for the establishment of a memorial hall for the victims of the Nanjing Massacre committed by the Japanese Imperial Army. In 1997, on the 60th anniversary of the Nanjing Massacre, Lin Boyao, along with other overseas Chinese in Japan and Japanese youth, co-founded the "Japan National Liaison Council for the 60th Anniversary of the Nanjing Massacre."

Concurrently, he has long focused on issues such as the forced abduction and compulsory labor of Chinese workers by Japan during World War II, as well as research into the Chinese victims of the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake and the subsequent atrocities, helping victims and their families seek redress and defend their rights. He once stated that revealing historical truth and upholding justice for the Chinese compatriots who suffered during World War II is his lifelong mission.

This year, on September 18th, the Heilongjiang Provincial Archives legally released a special collection of files on the "Japanese Imperial Army's forced conscription and enslavement of Chinese laborers," using irrefutable original documents to confirm the war crimes and atrocities against humanity committed by Japanese militarism. On that day, Mr. Lin Boyao traveled specifically to the Memorial Hall for Martyrs and Laborers Killed in Japan at the Tianjin Martyrs Cemetery to participate in a memorial ceremony, commemorating the "Hanaoka Uprising" that Chinese laborers launched on Japanese soil 80 years ago, unable to endure the abuse. During his conversation with Guancha, Mr. Lin specifically stressed his sincere hope that Japanese friends and the younger generation in China would visit the site to remember those Chinese people who suffered and died during Japan's war of aggression.

Editor's Note: From 1944 to 1945, Japanese aggressors forcibly conscripted 986 Chinese prisoners of war and laborers to perform arduous work at the Hanaoka Mine in Akita Prefecture. On June 30, 1945, 700 Chinese laborers launched a revolt, which the Japanese side suppressed with 20,000 military police. Statistics show that 419 Chinese laborers were killed or tortured to death there within a year, an incident historically known as the "Hanaoka Massacre" or "Hanaoka Uprising."

The National Day on October 1st is approaching, and we will celebrate the 76th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China. Today, the Chinese people live with dignity, contributing to national development and world progress. Even though the historical trauma cannot be erased, we continue to urge perpetrators to admit their mistakes, reflect deeply, and apologize sincerely. As Mr. Lin Boyao stated, victims have the right to express anger and hatred, but the ultimate goal is not retaliation in kind, but to clearly convey these emotions to the perpetrator nation and explore a path of peaceful coexistence that prevents such incidents from recurring.

Image Captions: File photo: Lin Boyao

The Old Overseas Chinese Are Not Silent

Guancha: Hello Mr. Lin, thank you very much for speaking with Guancha. Could we begin by discussing your recent activities? How is your health lately, and what keeps you busy? China recently held a grand commemoration for the 80th anniversary of the victory of the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War; did you participate in any domestic memorial activities, and what were your feelings?

Lin Boyao: I am already 86 years old, and though I am no longer in a state to participate in activities everywhere, I will be going to Tianjin tomorrow (September 16th). Tianjin is where the remains of many forcibly conscripted Chinese laborers who died in Japan are interred; their remains were repatriated from Japan during the 1950s and 1960s. We will hold a memorial service there for the Chinese laborers who died in Hanaoka (Note: located in Akita Prefecture, Japan) and various other places in Japan, as well as for laborers who passed away on the Chinese mainland.

Ten years ago, on the 70th anniversary of the victory of the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War, I attended the military parade in Tiananmen Square, which left a profound impression on me. Ten years later, the grand commemorative activities held this year for the 80th anniversary of the victory were also deeply moving for us overseas Chinese.

I believe it is a good thing that China has developed to be so strong today and is confidently showcasing this strength to the world. This clearly declares that we will no longer suffer aggression from imperialists as we did in the past.

During the 70th anniversary of the victory of the Anti-Japanese War, I watched the military parade together with war victims from Nanjing; they were shedding tears while joyfully saying, "We will never be bullied by Japanese militarism again." I felt the exact same way.

Guancha: While researching, I discovered that a preview screening of the documentary The Old Overseas Chinese Are Not Silent, which features you as the protagonist, was held in Japan last year, although the film had not been fully completed at that time. Has the production been finished this year? Could you tell us about the film's origin, theme, the main creative personnel involved in its production, the filming process, and the subsequent plans? Did you encounter any obstacles or difficulties during this process?

Lin Boyao: Thank you for your interest in our work. We did not encounter any particular difficulties or obstacles during the filming process.

This documentary was planned by friends in Japan, who chose to present the appeals and aspirations that Chinese residents in Japan wish to convey to Japanese society through the medium of a film or documentary, using the story of an old overseas Chinese named Lin Boyao—myself. They filmed my birthplace, Tanba, Kyoto, Japan, as well as my recent activities. The finished film is expected to be completed early next year.

The general reaction to the documentary preview was very positive, with some hoping that I, Lin Boyao, would speak more. There were also people who claimed, "Japan's aggression was not entirely bad; there were good aspects, too"—they made this remark, to which my reply was that Japanese militarism's aggression against China yielded absolutely no benefits; even if there appeared to be a good side, it was merely superficial, and the truth is that it caused tremendous sacrifices for the Chinese people, a fact that these critics fail to see.

Image Captions: Video screenshot from the documentary The Old Overseas Chinese Are Not Silent

"Shina-jin" and "Qing Slave": As a Child, I Did Not Understand Why

Guancha: We look forward to seeing the documentary soon. This year marks the 80th anniversary of the victory of the Anti-Japanese War. When Japan surrendered 80 years ago, you must have been in Japan; do you have any recollections of the scene and your feelings at that time, and could you share that story? Born in Japan in 1939, with your parents having moved to Japan earlier to seek a living, you have virtually lived through all the history since Japan's full-scale invasion of China. What impact have these experiences had on your life and choices?

Lin Boyao: My father and mother came from Fuqing, Fujian Province, China, and my father arrived in Japan in 1913. At that time, China was extremely poor, suffering both from the aggression of imperialist powers and from various natural disasters and famines. Unable to make a living in China, my father had no other choice but to come to Japan.

I was born in Tanba, Kyoto, Japan, but I suffered from various forms of bullying and discrimination from a young age, being called "Shina-jin" and "Qing slave." At the time, even Korean children would grab me, demanding, "We are Japanese, you are Shina-jin, apologize to me," and bullied me unreasonably. As a child, I was extremely distressed by this. I did not understand why Chinese people faced such bullying and discrimination in that era; only later did I learn that it was because our country was too weak and poor, an era when many Chinese people could not live with dignity.

What is often mentioned now is the "Coolie (クーリー) trade" that existed in the Fujian and Guangdong regions, where people had no work to sustain themselves. After the abolition of the slave trade, the Coolie trade effectively turned many Chinese people into slaves, who were sent to the United States, Central and South America, and other parts of the world to be exploited by capitalists. I believe this tragic history served as the background, but as a child, I did not understand why I was called "Shina-jin" and "Qing slave," and was consequently bullied.

I recall that when I was young, my parents worked as itinerant merchants, selling cloth. An itinerant merchant is someone who carries cloth or fabrics on their back, walking from one village to another, from one town to the next, to sell their goods. Once, when they passed by a farm household they regularly visited, the owner came out and said, "You Shina-jin, don't come here anymore."

At that time, my mother was out selling goods, holding my young hand. Suddenly, a big man rushed out of the farmhouse and yelled at us, "You Shina-jin, get out of here." Then, he released the large black dog they kept to chase us away and incited it to bite us.

My mother was utterly terrified and pulled my hand, running away. We scrambled along the embankment, which was muddy, overgrown with weeds, and extremely rough, causing the cloth on my mother's back to suddenly slip and fall into the paddy field. At that moment, we heard the dog barking behind us. My mother, in a panic, urged me, "Hurry down and pick up the cloth that fell into the field!" So, we both went down into the field—which was flooded with water for planting rice—retrieved the cloth stained with mud and water, and escaped to the other side of the embankment to evade the large dog's pursuit. The dog was chasing us and barking furiously behind us; the memory is still vivid and chilling to this day.

Afterward, my mother took the cloth and brought me to the mountain, where she washed the cloth clean in the mountain stream and hung it on a tree; if it were not washed and dried promptly, the cloth could not be sold. As she hung the bolts of cloth among the branches, my mother was sobbing and crying with anger, muttering "oh dear, oh dear," as tears streamed down her face. I looked up and gazed at the tears rolling from my mother's eyes, confused and wondering: why was this happening?

Koreans were also subject to bullying, but they redirected this bullying onto the Chinese. However, I can understand this situation. Koreans had indeed experienced tremendous suffering, having been placed under Japanese colonial rule, and were brought or forcibly taken to Japan, where they endured great hardship.

Later, during my middle school years, I learned about the "Hanaoka Incident" in Japan. This incident stemmed from a revolt launched by Chinese people, who had been forcibly transported from China to perform slave labor in the Hanaoka area of Akita Prefecture, as they could no longer bear the abuse and sought to uphold their human and national dignity.

The incident occurred on June 30, 1945. I only learned about this history in middle school and was deeply shocked at the time—it showed me that the Chinese people were also a nation capable of resistance. Although I never attended a formal Chinese school, the Hanaoka Incident and the forced labor cases gradually instilled in me a sense of anger and national sentiment, serving as a life lesson.

Guancha: You were still very young in 1945; do you have any recollections of Japan's surrender and defeat, or do you remember any scenes or stories from that time?

Lin Boyao: I was living in Tanba, Kyoto, deep in the Japanese countryside. Although I did not hear news of Japan's defeat as reported in the newspapers, I immediately felt a change in the attitude of the villagers. Subsequently, the so-called American occupying forces appeared, with officers arriving in open-top jeeps in our village deep in the mountains of Tanba.

I assume it was because they knew my father was Chinese, that when the villagers learned the US forces were coming and would look for my father, they came to him, pleading with him to tell the Americans that they had not bullied our family and had done nothing wrong. The villagers—especially key figures like the village head, the police officer, and the postmaster—all hid in the mountains. They were very afraid of the American occupying forces. However, we did not speak ill of the Japanese people.

This experience made me deeply feel that the times had truly changed. From that point on, I realized we had entered a different world.

Later, my family moved to Kyoto, where my father served as the first president of the Kyoto Overseas Chinese Federation. These memories remain fresh today.

At that time, my parents' generation and overseas Chinese associations across the country proudly displayed the flag representing the Chinese government of the time in front of their homes, an act that had been extremely dangerous in the past. Yet, in response to this, some former Japanese soldiers launched attacks and instigated conflicts, committing acts of violence based on the claim that "Japan did not lose the war," resulting in assaults on Koreans and Chinese people.

If we reflect, before that time, Chinese people residing in Japan were treated as "enemy aliens" and subjected to bullying and discrimination. Just one year before 1945, in 1944, 13 key members of the Kobe Fujian Itinerant Merchants Association were successively arrested and tortured by the Japanese "Tokko" or "Special Higher Police" (Tokubetsu Kōtō Keisatsu), based on groundless accusations such as "engaging in espionage activities." In other words, the itinerant merchants were subjected to torture because of Japanese police's fabricated charges, such as "itinerant merchants gathering various intelligence in cities or villages and sending it back to the Chinese mainland."

Ultimately, two of the 13 individuals died in prison, and four passed away shortly after their release. The family of one victim was notified that "your father is no longer useful, come and take him away," and when his wife arrived at the Osaka Police Station, she was handed her husband's corpse, whose intestines had ruptured in his abdomen.

Later, according to the accounts of other survivors, they were subjected to extremely brutal torture, which included not only severe beatings and the insertion of pencils under their fingernails but also being hung in mid-air and having their heads forcibly submerged in water during interrogation.

In fact, this situation was quite common at the time, as Chinese people were deemed "enemy aliens" and were arbitrarily arrested or unfairly treated by the police. However, August 15, 1945, was a watershed moment; after that date, such incidents vanished, and the Chinese people could finally hold their heads high.

This incident is known as the "Kobe Fujian Itinerant Merchants Persecution Incident." Last year marked the 80th anniversary, and we held a memorial ceremony at the Guandi Temple to remember them, with everyone vowing never to allow such an era to be repeated.

Victimized Nations Have a Historical Obligation to Express Their Pain, Anger, and Hatred

Guancha: In that era, not only did the people in China endure the humiliation of war, but Chinese people residing in Japan also experienced immense suffering. Given this year's 80th anniversary of the victory of the Anti-Japanese War, we are paying close attention to the Japanese government's statements. However, Shigeru Ishiba was reportedly prepared to give a speech but was prevented from doing so by the Liberal Democratic Party. Furthermore, the Japanese government reportedly urged some countries not to participate in the September 3rd military parade hosted by China. What is your view on these actions by the Japanese political establishment, and do they indicate a significant shift in the atmosphere and perceptions within Japanese society?

Lin Boyao: Japanese society has undergone a massive change in the last decade, with US support being one of the contributing factors. The specter of Japanese militarism is being resurrected, and the shadow of Japanese imperialism is growing heavier. It is regrettable that this time the Japanese government went so far as to request that other nations exercise "self-restraint"—not to attend the commemorative events hosted by China on September 3rd, a matter even reported in Japanese newspapers. This is simply intolerable.

China held a military parade on September 3rd to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the victory of the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War. Perhaps this is exactly the scene the militarists did not wish to witness; they are genuinely afraid—afraid of the growing strength of the people's righteous power.

I watched the parade, and the spectacle was truly magnificent, filling my heart with immense pride. I was particularly impressed when President Xi Jinping emphasized that "history warns us that the destiny of mankind is closely linked," that "all countries and nations should treat each other equally and coexist in harmony," and when he pointed out that "China will take the lead in building a community of shared future for mankind."

Ten years ago, I attended the 70th-anniversary parade. At that time, President Xi Jinping mentioned in his speech on the Tiananmen Rostrum: "The Chinese people suffered aggression, humiliation, and plunder by great powers for more than a hundred years, but the Chinese people did not learn the logic of the jungle from this experience; instead, they became even more determined to safeguard peace. China will never impose the painful experiences it has suffered upon other nations."

Those words deeply moved me; it is truly remarkable for the leader of a victimized nation to articulate such a position.

I consistently maintain the view that perpetrator nations and perpetrator states should reflect on the past, admit their errors, apologize or offer compensation to Asian victims, and guarantee that such incidents will never happen again. Concurrently, victimized nations and victimized states, including their leaders, have a historical obligation to express the pain, suffering, anger, and even hatred brought upon them by imperialism and militarism; without this expression, the perpetrator nations will never understand.

How should this anger and hatred be managed? Certainly not in the form of revenge, but by clearly conveying these emotions to the perpetrator nation and exploring a path of peaceful coexistence that prevents such incidents from recurring. In this sense, I believe China may be too restrained. Whether it is the issue of forced labor conscription or the massacre of Chinese people during the Great Kanto Earthquake—where victims were killed with firearms, bayonets, axes, or spears—I cannot shake those moments from my mind. These historical facts must be known by both perpetrators and victims. It is critically important to determine how victimized nations and perpetrator nations should move forward together to prevent such a tragic history from repeating itself.

As an overseas Chinese residing in Japan, I am deeply troubled by the current state of Japanese society. In recent years, the facts of aggression committed by Japan as a perpetrator nation have been gradually diluted in school textbooks. Just last year, the so-called "Reiwa textbooks" were released, whose content attempts to conceal the facts of aggression, such as the Nanjing Massacre. It is alarming that the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) would approve such textbooks. Even more frightening is that the Japanese cabinet and the mayor of Hiroshima are re-endorsing the wartime "Imperial Rescript on Education," attempting to integrate it into current school education, the central tenet of which is "to dedicate one's life to the Emperor." These are all phenomena that cause me great concern.

As you mentioned, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are undeniable facts, but they instill in the next generation the notion that "we were the victims in this war of aggression." Objectively, the ordinary people of Japan did suffer from the war, yet if one visits the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, one finds a complete absence of explanation regarding why the atomic bombs were dropped. What exactly happened there at the time? What had happened earlier in Nanjing and Northeast China? These facts are completely ignored, and only the victim identity is emphasized, which I believe is wrong and even intentional.

Now, they are in turn peddling the baseless "China Threat Theory," creating public opinion that suggests "China might invade," and fostering this atmosphere through various means. Specifically, former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's illogical assertion that "A Taiwan contingency is a Japanese contingency, and a Japanese contingency is a Japan-US contingency" has already fueled Japan's military expansion. This makes me feel that we are surrounded by peril.

On August 8, 2023, former Prime Minister and former Vice President of the Liberal Democratic Party, Taro Aso, stated during his visit to the Taiwan region that "we must be prepared to fight with China," encouraging some "Taiwan independence" elements. However, in documents such as the Sino-Japanese Joint Statement (1972), Japan had originally committed to understanding and respecting China's position—that Taiwan is the sacred territory of China—yet now it asserts the "undetermined status of Taiwan," claiming that "although Taiwan was relinquished by us, its destination was not mentioned." Such behavior is a manifestation of the colonialist nature.

Image Captions: US Marine Corps soldiers conducting a machine gun setup drill at Camp Hansen, Okinawa, Japan, in preparation for "Resolute Dragon 25" (Resolute Dragon Twenty-Five) exercise.

On September 11, the Japan-US joint military exercise "Resolute Dragon 25" was held, with approximately 14,000 soldiers from the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) operating together with the US military. A large number of JSDF weapons and long-range missiles have been deployed in Kyushu and Okinawa, and the dangerous flight activities of the Osprey (Vertical Takeoff and Landing aircraft) have provoked opposition from residents in various areas. In particular, the Japan-US joint exercise "Keen Sword 25," which began on October 23 last year, lasted for ten days and involved 45,000 JSDF personnel and US military forces. This was the largest Japan-US military exercise in history, and they designated China as the imaginary enemy nation for the exercise.

I consider this entirely provocative behavior that poses a massive threat to China and Asia, yet the Japanese media has maintained almost complete silence on the matter. The Japanese side is deftly manipulating public opinion, particularly by using the baseless "China Threat Theory" to generate anti-China and anti-Chinese sentiment within Japan, which fills me with great anger and worry.

Noble talk such as everyone bearing historical responsibility for the next generation and not repeating past mistakes is simply absent from the rhetoric of Shinzo Abe. What we demand today is not merely an apology, but profound introspection from Japan, and a joint deliberation between victimized nations and Japan on the issue of peaceful coexistence to prevent such a war from being re-staged. Regrettably, Shinzo Abe's statements did not reflect any consideration for peace in Asia. Therefore, I harbor extreme anxiety and anger regarding the current trends in Japan.

The "Imperial Rescript on Education," which the Japanese cabinet endorsed in a cabinet meeting, was used during World War II to teach children to sacrifice their lives for the Emperor. This represents a dark chapter in history, but today, this educational philosophy continues in some schools in Japan, and the mayor of Hiroshima has even expressed support for it, which is infuriating. We must prevent the resurrection of Japanese militarism.

Guancha: I wholeheartedly agree; the true purpose of our continuous reflection on the war is for the next generation, so they know how to view this history and prevent it from ever repeating. For this 80th anniversary, have any Japanese civil society organizations held activities?

Lin Boyao: We held a memorial ceremony for the "Hanaoka Incident" in Tianjin, in which victims' families and friends from Japan participated together to commemorate this history. In the 1950s and 1960s, with the joint assistance of many Japanese and Korean friends, the remains of Chinese laborers who died in Japan were repatriated to China. That was a profoundly moving period in history, and we must remember that era and vow to work hand-in-hand with the peoples of China and Japan to move forward.

As I live in Japan, I also communicate with many brave and righteous Japanese friends; there are indeed many people of conscience and sincerity in Japan who are well-informed. For this very reason, I have never lost hope.

Image Captions: Lin Boyao speaking at the memorial event for martyrs and laborers killed in Japan at the Tianjin Martyrs Cemetery in 2011. Tianjinnianwang.

The more than 2,300 sets of remains of Chinese laborers repatriated from Japan are interred in the Memorial Hall for Martyrs and Laborers Killed in Japan at the Tianjin Martyrs Cemetery. When one sees with their own eyes the remains of those laborers who died from abuse in Japan, Japan's past deeds are clearly revealed. I sincerely hope that Japanese friends and the younger generation in China can all go there to see it.

Guancha: Before our conversation today, you sent me a photograph containing materials related to the Nanjing Massacre. Perhaps many Chinese people are unaware that you proposed the establishment of a memorial hall for the victims of the Nanjing Massacre very early on and have made great contributions to it, in addition to continuously collecting a large amount of evidence and materials in Japan. What is the current status of material collection in recent years, what are the main channels used for collection, and are there others involved besides yourself?

Lin Boyao: After tracking the Hanaoka Incident, I felt an urgent need to research the issue of the Nanjing Massacre. Both Chinese and Japanese scholars have been presenting their arguments based on their respective evidence and historical contexts, but I wanted to hear what people who were physically present at the massacre site experienced, whether they were victims or perpetrators. Nanjing has countless victims, and we have collected a large amount of victim testimonies. However, few people involved in the research on the Nanjing Massacre have focused on the historical circumstances of the perpetrators.

In 1997, we united many Japanese civic groups concerned about the Nanjing Massacre to establish the Japan National Liaison Council for the 60th Anniversary of the Nanjing Massacre, of which I am one of the representatives. Our first step was to seek out Japanese veterans who had participated in the Battle of Nanjing and record their testimonies. Over nearly five years, we recorded more than 200 testimonies and captured them on video. Every December, we convene testimony gatherings, inviting victims, their families, or researchers from Nanjing to share the truth of the Nanjing Massacre with the Japanese public. I believe we have achieved a certain degree of success in this area.

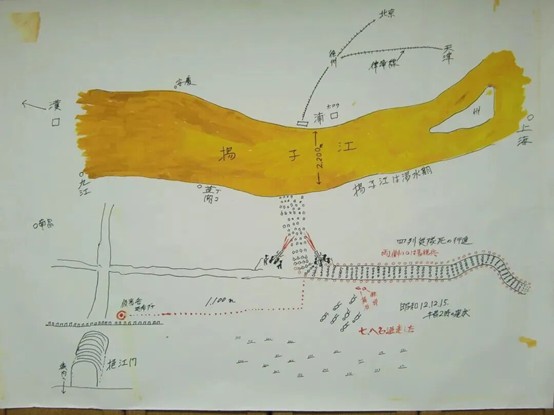

In fact, the image I just sent to you was provided by the family of a soldier who participated in the Battle of Nanjing, and this material has not been officially published or released. The records of the Nanjing Military Tribunal show a number of victims exceeding 300,000, which may actually be as high as 340,000, yet Nanjing Massacre denialists dispute this figure. Among the cases we have compiled, the content depicted in this drawing is chilling. The painting was created by a soldier who participated in the Battle of Nanjing. He stated that "if I do not commit this matter to writing, I will not be able to rest in peace," and so he personally wrote and narrated the contents of the drawing.

Regrettably, this Japanese soldier has passed away, and we obtained this drawing from his surviving family. The scene depicted in the drawing occurred at 2:00 AM on December 15, Showa 12 (1937), which was two days after the fall of Nanjing.

Image Captions: Scene of the Japanese army massacring Chinese prisoners of war at 2:00 AM on December 15, 1937, as depicted by a Japanese soldier; provided by Mr. Lin Boyao.

The drawing depicts the barracks located near Yijiang Gate in Xiaguan on the Yangtze River, which served as accommodation for Japanese garrison officers and soldiers. This location was also the headquarters (Teihakusho Shireibu) for unloading supplies when weapons and ammunition were transported from Japan to Nanjing. The soldier signed "Kajitani" in the drawing is the one who created this illustration.

This barracks was only 1,100 meters away from the soldiers. On the night of December 15th, after hearing intense machine gun fire, he and a subordinate named Keibe came outside their dormitory. The sight before him was shocking: captured Chinese prisoners of war, lined up in four columns, were tightly surrounded by Japanese soldiers and forced toward the riverbank, with heavy machine guns continuously sweeping fire from both sides. It was like a conveyor belt, with Chinese people being killed in batches. Most mass killings involved gathering people in the center and shooting them from the periphery, or lining them up in groups of ten or twenty and pushing them into the river.

However, at this location, the Japanese soldiers completely encircled the prisoners of war they had escorted and forced them to march toward the Yangtze River; it was a death march, with machine gun nests ahead continuously firing upon them. He witnessed more than 3,000 Chinese soldiers being murdered on the night of December 15th—that night, the moonlight in Nanjing was bright, and the scene was clearly visible.

When he saw a Chinese soldier walk past with composure, he almost involuntarily wanted to salute him. The resolute determination revealed by this Chinese soldier was all recorded in his hand-written notes.

This drawing depicts the situation after many Chinese soldiers finally surrendered at that time. After disarming, they were executed en masse by Japanese machine guns. This was the most brutal method of killing. In fact, this atrocity occurred multiple times from the fall of Nanjing on December 13 until the end of the year. This soldier was drawing the scene for the first time with his own hands. I sincerely hope everyone becomes aware of this; it is a truth that must be known.

Hatred Should Be Allowed to Be Expressed, But Must Also Be Transformed into a Force for World Change

Guancha: For those without direct war experience, the brutality of war is primarily understood through films, historical records, and other materials. This brings to mind a recent controversy in China surrounding the film Nanjing Photo Studio, released this year, which received praise but was also criticized by some for being too cruel, promoting hatred, and being unsuitable for minors to watch. Having personally endured the harshness of war, what are your thoughts on balancing the public's perception of history with the present and the future? How can successive generations raised in times of peace come to understand war and peace, hatred and tolerance?

Lin Boyao: I have not yet seen Nanjing Photo Studio, but I heard from the news that it caused a great stir in China. The Nanjing Massacre is, of course, a historical fact; at that time, the Japanese army killed Chinese people as if they were ants, perpetrating rape and abuse. Japanese soldiers even took pictures of those scenes themselves, as if it were an act of glory. This is already known to scholars and the general public, but we must make more people aware of these facts, despite their extreme cruelty.

The purpose of our efforts is absolutely not to incite hatred, but to enable more people to see the facts. These facts naturally encompass anger, grief, and hatred, but these are indispensable human emotions, and their expression should be permitted.

This was caused by past Japanese militarism, and we must seriously consider how to approach the Japanese people and Japanese society, who are the origin of these acts—we must not resort to hatred, but rather help Japanese society recognize these historical facts. Otherwise, the Japanese people will never understand, thinking, "Ah, so something like this also happened?" What the Japanese public knows is the celebration of the fall of Nanjing that was mobilized across the country at that time. People slightly older than me personally experienced this part of history. Their understanding of Nanjing ends there, and they must be informed that behind the Japanese celebrations of Nanjing's fall, countless Nanjing citizens were being massacred.

However, we must absolutely not retaliate with hatred; instead, we should focus on preventing this tragedy from recurring. The Japanese people are still calling out today, saying, "We neither want to be killed nor to kill others. We must never allow history to repeat itself."

In response to this, I believe we must earnestly explore the path forward, uniting people of conscience and goodwill both domestically and internationally to jointly engage in a serious discussion on how to build a new era in which China and Japan never wage war. Our task is to etch history into our hearts, rather than inciting hatred, and to appeal to the Japanese people to jointly consider how we can work together to construct an Asia that never repeats the catastrophe of a war of aggression.

Undeniably, hatred is one of humanity's important emotions. However, we should not stop at hatred itself; instead, we must jointly contemplate how to transform this hatred into a driving force to prevent such wars from happening again and to promote world change. Merely confining ourselves to the level of "not dwelling only on hatred" would likely lack persuasive power.

Survivors Spoke Not of Heroic Deeds, But of Extremely Agonizing and Painful Experiences

Guancha: Aside from the Nanjing Massacre, another highly important part of your work concerns the Chinese laborers in Japan at that time, such as the Hanaoka Incident you mentioned earlier. My research shows that the lawsuit filed by Chinese laborers against the Japanese company Mitsubishi Materials for compensation concluded in 2016, and you were one of the case negotiators; this case garnered significant attention in China. Could you discuss the background of your involvement in this Chinese laborer compensation case and the difficulties you faced? Nearly ten years have passed since then; have any related cases progressed in recent years?

Lin Boyao: The reasons for the forced conscription of laborers and the Hanaoka Uprising were mentioned previously. In 1987, I learned that Mr. Geng Zhun, a survivor of the Hanaoka Incident and former captain of the Zhongshan Dormitory, was still alive, so I invited him to visit Japan to attend a memorial service held in Odate City, Akita Prefecture. Following that,

The Kobe Overseas Chinese General Association invited him to Kobe, hosted a reception for him, and held a symposium together.

Firstly, most overseas Chinese in Japan were aware of the Hanaoka Incident and the fact that forced labor conscription and compulsory labor had occurred at 135 work sites across Japan. The overseas Chinese who had participated in the repatriation of the remains also actively took part. For this reason, everyone wanted to invite the survivors to share their stories.

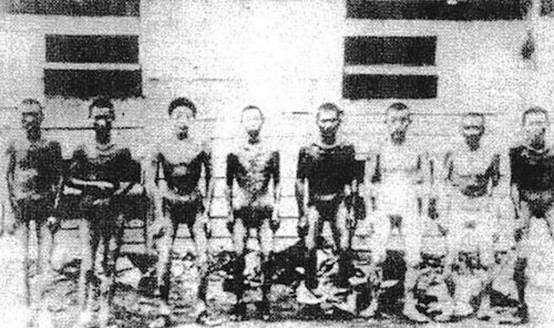

Image Captions: File photo: Chinese laborers surviving the Hanaoka Mine in Akita Prefecture undergoing medical examinations by the US military after the war. China Youth Daily

At the time, everyone was all ears, wanting to hear him recount the story of how the Chinese laborers bravely resisted in the Hanaoka Uprising despite the hardships. Yet, when he began to describe his experiences, he was crying profusely, which stunned all of us present, as he spoke not of heroic deeds, but of his own extremely sorrowful, painful, and agonizing personal experiences.

Another survivor traveling with him, Mr. Liu Zhiqu, who had been stranded in Hokkaido, also broke down sobbing when speaking of the past. Under the shadow of compulsory labor, what emerged was nothing but tears, wounds, and profound grief, which made us realize the extent of the terrible torment, abuse, and death suffered by countless laborers.

Therefore, my younger brother and I decided to take action together with our Japanese friends to heal the deep wounds left in the hearts of the victims of the Hanaoka Incident. In 1988, I discussed with Mr. Geng Zhun and decided to meet with the survivors of the Hanaoka Uprising in China. The following year, Mr. Liu Zhiqu and I traveled to China and gathered with several Hanaoka Uprising survivors. At that time, they also inquired about the judicial outcome of the US military's prosecution of the Hanaoka Incident at the Yokohama B/C-Class Military Tribunal in 1946, as well as the attitudes of the Japanese government and Kajima Construction at the time.

In the past, the Japanese government had asserted in the Diet that "Chinese laborers were contract workers," refusing to acknowledge the fact of forced abduction. Kajima Construction, in its defense at the Yokohama B/C-Class Military Tribunal, claimed that the company would kill cattle and sheep to reward the workers during the New Year, that Chinese laborers would be immediately taken to the hospital if they were sick or injured, and that their wages were deposited in a certain bank or post office. These details came from the trial records of the Yokohama B/C-Class Military Tribunal. When I recounted these details to the survivors, they were all extremely angry, finding these complete distortions of the facts to be unacceptable.

Image Captions: Protest march in Japan against the Hanaoka Massacre; Lin Boyao is the first person on the right in the front row.

Consequently, the survivors shifted their demand to compensation, initiating requests to the perpetrator company, Kajima Construction, and the Japanese government, and submitting an open letter requesting compensation to Kajima Construction for the first time in 1989. Ultimately, a settlement was reached with Kajima Construction in November 2000, which involved a one-time payment of 500 million yen to the 986 victims. As for the lawsuit against the Japanese government, they filed suit in June 2015, together with victims of forced labor at Osaka Port, but ultimately lost the case. Nevertheless, the court acknowledged that the forced conscription of Chinese laborers was part of a Japanese national policy, and the Japanese government bore significant responsibility. However, because China had waived reparations in the Sino-Japanese Joint Statement (1972), this particular compensation claim was not resolved.

Mitsubishi actually forcibly conscripted over 3,700 Chinese laborers. When we presented a negotiation request to the Mitsubishi Group, stating, "Please resolve this matter," they responded that for negotiations to proceed, the Japanese government must be involved before the company would consider it. However, the Japanese government consistently refused to come forward, citing the Sino-Japanese Joint Statement.

At that time, the families of Mitsubishi's victims staged protests in front of Mitsubishi companies across China. During the protests at Mitsubishi Materials' headquarters in Shanghai, they demanded that Mitsubishi's Japan headquarters take responsibility for compensating the forced laborers; these efforts were made by the victims' families themselves.

Mitsubishi appeared to be quite troubled by these direct protests, as China is an important market and a source of raw materials for them. Eventually, Mitsubishi indicated that if the protest activities in China ceased and information was no longer disclosed to the media, they would listen to the victims' demands.

Ultimately, Mitsubishi paid compensation of 100,000 Chinese Yuan (RMB) (approximately 2 million Japanese Yen) to each victim's family, and simultaneously permitted the families to travel to Japan to participate in memorial activities at the sites where their ancestors were forced into slave labor. Furthermore, a Fund Management Committee was established, with the victims' side sending six representatives, of which I am one. As of now, over 1,900 victims have received the compensation.

In fact, Mitsubishi strongly resisted the term "compensation." Since Mitsubishi had won all the lawsuits filed against it in Japan, they argued that this was not compensation, but rather "evidence of apology."

However, some people in China mistakenly believe that Mitsubishi voluntarily apologized and paid compensation to the victims, which is not the case. This outcome was the result of the victims and their families courageously stepping forward to speak out and fight for their rights.

Approximately 1,500 family members of the victims are still traveling to Japan in batches to participate in memorial activities. In this regard, Mitsubishi has promised to pay each person a subsidy of 250,000 Japanese Yen, separate from the compensation, as an additional expense. This is certainly a good development. Although some companies have paid compensation, the majority have either ignored or refused to do so, and the victims are unable to speak out.

I deeply regret that the Japanese government has still not acknowledged its grave responsibility for the forced labor conscription incidents that occurred at these 135 work sites. In fact, such forced conscription could not have happened without the assistance of the Japanese military, and the Japanese government, which issued the orders, should rightfully bear the primary responsibility. I hope the Japanese government will come up with a decisive solution and issue a formal apology.

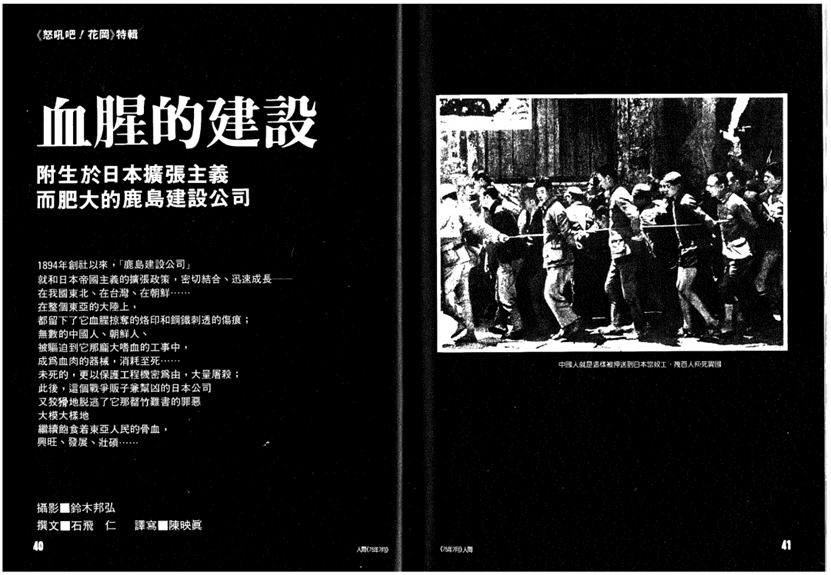

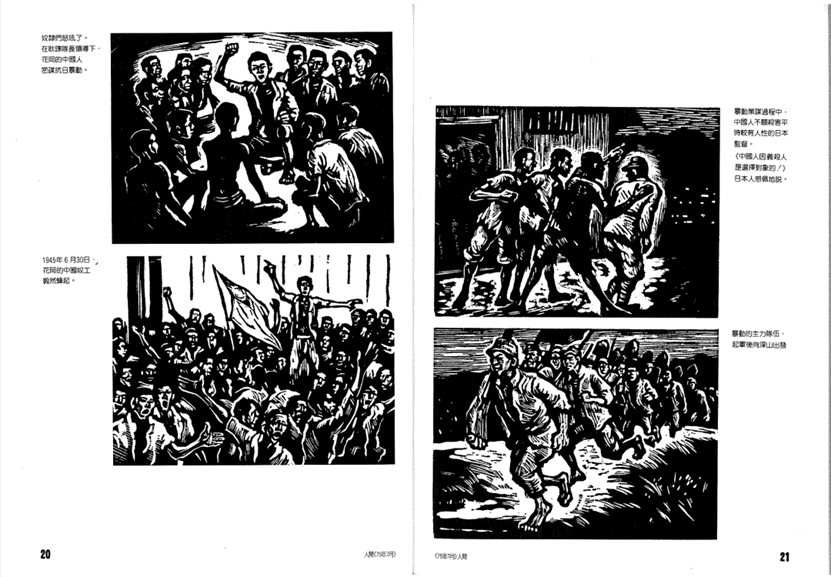

Image Captions: The Taiwan region magazine Renjian (Humanity) launched a special feature in 1986 titled "Roar, Hanaoka!", reviewing the history of the Hanaoka Uprising through documentary writing and woodcuts.

What I want to state is that approximately 38,000 Chinese laborers were forcibly sent to Japan. According to the report by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 6,830 people died, but a more accurate count suggests the death toll is approximately 8,000–9,000 people. Currently, more than 2,300 sets of Chinese laborers' remains have been repatriated and interred in Tianjin, meaning there are still over 6,000 sets of remains lying on Japanese soil.

On the Chinese mainland, 15 million Chinese people were forcibly conscripted and subjected to compulsory labor in the Northeast region alone, with conservative estimates placing the death toll potentially at three to four million. Across the whole of China, tens of millions of people were subjected to compulsory labor, and the number of deaths reached several million. Some Japanese researchers even believe the deceased could total as many as ten million. However, this issue has not received the attention it deserves in Japanese society, and Chinese people, including myself, have also been negligent in this regard; more researchers should have come forward to investigate the truth and push for a thorough investigation of historical facts, but this has not yet been achieved, which is truly regrettable.

What is particularly heartbreaking is that during the period of rapid economic development, some "forced detention centers" and "pits of ten thousand corpses" were demolished and buried. I hope local governments, Chinese scholars, and the families of the victims will collectively pay attention to these issues.

The Japanese Government Has Refused to Discuss the Great Kanto Earthquake and the Atrocities in Japan for Over a Century

Guancha: How did you become aware of the history of the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake and the Kanto Massacre? This history may not be widely known in China. Many people might know that Koreans in Japan were massacred, but hundreds of Chinese people were also victims. Over the years, you have been campaigning for this historical atrocity, holding memorial events in Japan and so on. This historical tragedy has not received the attention it deserves in China, which should serve as a wake-up call for us. Are activities related to this history still ongoing these years, and could you share some details?

Lin Boyao: A total of 758 Chinese people who were massacred during the Great Kanto Earthquake were officially registered. They did not die from natural disasters, but were brutally killed by the Japanese military, police, and populace.

My father was trading in Tokyo when he experienced the Great Kanto Earthquake on September 1, 1923. Rushing back to his apartment, he found fires erupting everywhere. Subsequently, a rumor circulated throughout society that Koreans were setting fires, urging everyone to be vigilant. In fact, "Self-Defense Groups" (Jikeidan) began to be organized and mobilized from the evening of September 1. When my father learned of this situation, he realized that both Chinese and Koreans would be under threat. In the urgent circumstances where phone contact was impossible, he quickly gathered 12 fellow provincials near Asakusa, Tokyo. As the situation was highly perilous, my father, together with my mother (a total of 13 people), went to the Metropolitan Police Department (Keishicho) to seek protection and apply for a pass.

However, the Metropolitan Police Department had also been affected by the earthquake, and they claimed they were helpless, allegedly unable to even find writing implements or seals. After night fell, my father overheard someone saying, "There are Chinese people gathered over there," and "Drag those guys out," sensing the imminent danger. He then gathered all his fellow provincials and, that evening, led them to rush into the temporary office that the Metropolitan Police Department had set up in the nearby Hibiya Park, where they took shelter for the night.

After martial law was declared on the afternoon of September 2, the Military Police (Kenpeitai) arrived. They issued passes for them, replacing the police. I still do not know what was written on the passes, but it probably contained terms such as "Zhīnà people" or "Zhīnà Republic citizens". Even though the Republic of China had been established at that time, the Japanese government did not use the formal name "Republic of China" but instead used the insulting appellation "Zhīnà Republic".

Many of the victims of the Great Kanto Earthquake came from poor villages in the Gaodi mountainous area of Wenzhou, with over 400 victims from Wenzhou alone. Furthermore, many people from places such as Fujian and Guangdong were also massacred. Chinese students in Japan at the time compiled a survey list, enumerating a total of 758 people. According to the Independent News of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea (Daehan Minguk Joseon Imsi Jeongbu), which was located in Shanghai at the time, approximately 6,661 Koreans were brutally massacred.

Image Captions: After the Great Kanto Earthquake, a large number of Koreans and Chinese people in Japan were brutally murdered.

For more than a century, the Japanese government has consistently refused to discuss the massacres of Koreans and Chinese people. Initially, after the disaster, Koreans and some insightful individuals would hold memorial services, but all such activities were prohibited following the implementation of the Public Security Preservation Law in 1925, as if everything the Japanese government did at that time were correct.

The day after the earthquake, the Japanese government issued a circular to all administrative governors in the name of the Director of the Police Affairs Bureau of the Ministry of Home Affairs. The circular claimed that "Koreans are taking advantage of the earthquake near Tokyo to commit arson in various places, carrying bombs and pouring gasoline to start fires within Tokyo, and must be severely suppressed." It also required the establishment of Self-Defense Groups (Jikeidan) in all areas, which were then rapidly formed across the country. The number of Jikeidan in Kanagawa, Tokyo, and the surrounding Kanto region exceeded 3,000, and they massacred many Koreans and Chinese people. In the Ōshimachō Incident, the outstanding Chinese student Wang Xitian, who had been actively working to support Chinese laborers, was murdered by the military under the pretext of being an "anti-Japanese ringleader." He was a revolutionary who had participated in the May Fourth Movement.

Starting around 1920, the Japanese economy began to decline. As many factories closed and unemployment increased, Chinese laborers were viewed as people who were taking jobs away from the Japanese. The government demanded that the employment of Chinese people be prohibited and stopped, and it began arresting Chinese laborers in various places for forced repatriation. Japanese workers also demanded that the government and businesses refrain from employing Chinese laborers. In this way, Japanese officials and the populace collaborated to persecute and suppress the laborers who had come to Japan for work at the time.

At the time, the May Fourth Movement was surging in China, with anti-Japanese sentiment running high. Japanese hostility and vigilance towards the Chinese deepened, and the same was true for Koreans. The "Mutual Aid Society for Chinese Residents in Japan" (Qiáo Rì Gòngjì Huì), founded by Wang Xitian, helped laborers demand their wages and fight for pay raises and other rights, but this also incurred the resentment of Japanese entrepreneurs, labor agents, and Japanese workers. Consequently, on September 3, the military, police, and Jikeidan stormed the Chinese dormitory and gathered the Chinese residents onto a nearby square. When about 200 people had assembled, 300 Japanese workers, police, and soldiers surrounded them and beat them until they were killed. This collective massacre, known as the "Ōshimachō Incident" in Japan, is referred to as the "Atrocities in Japan" (Dōngyīng Cǎ’àn) by Chinese scholars.

Image Captions: At Kanmyōji Temple in Ōshimachō, the chief priest Watanabe takes out a wooden board from the altar, which is inscribed with words such as "Water-pouring offering for the spirits of the Chinese victims of the Great Kanto Earthquake during the Ullambana Festival." Lin Boyao said he searched many temples, but only this one accepted the request to commemorate the Chinese victims.

I urge everyone to come to Japan to mourn at the final resting place of the deceased. Next year, we will coordinate with the victims' relatives to travel to Japan to negotiate with the Japanese government and officially launch the campaign demanding recognition of the facts, an apology, and compensation.

In 1923, the Japanese Cabinet made a decision that the state should pay compensation for the massacres triggered by the earthquake. At the time, Korea had been fully occupied by Japan and was legally considered "Japanese," but the Chinese people were still foreigners. Therefore, the year after the earthquake, the Japanese government decided to pay the Chinese government a sum of 200,000 yuan, which is equivalent to approximately 8 million Japanese yen today. However, this matter was forgotten as Japan launched its war of aggression.

In 2023, for the 100th anniversary of the Great Kanto Earthquake, we held a joint memorial service for the massacred Koreans and Chinese people. I was one of the co-representatives of the memorial executive committee. Many citizens participated in the assembly, nearly 1,800 people, the vast majority of whom were Japanese. I believe that the conscience of the Japanese people and many insightful individuals will bring about a positive outcome, but there are still many tasks to be accomplished. Students studying abroad are also gradually joining this movement, with the hope that they will be the ones to disseminate the historical truth.

Guancha: Finally, turning to the present: First, how will the work you are engaged in continue in the future? The passing down of history is a relay race across generations. What do you want to say or what do you wish to call for to the younger generation? Second, due to the unique nature of your personal experience—being born and raised in Japan—you have deep feelings for both China and Japan emotionally, serving in some ways as a symbol of Sino-Japanese relations. Sino-Japanese diplomatic relations were established in 1978 and were followed by a honeymoon period. Since then, however, tensions have often flared up quickly between the two peoples over the slightest "spark." Sino-Japanese relations have sharply deteriorated in recent years and can now be described as frozen. Recently, there have even been xenophobic and anti-Chinese voices emerging on the Japanese internet and in political circles. The various activities you are involved in are not only about confronting the past but also about looking towards the future. Based on your personal experience, what are your views and expectations for the present and future of Sino-Japanese relations?

Lin Boyao: I was born in Japan and am now 86 years old. I have experienced many unpleasant things in Japan, but overall, I grew up in the Japanese climate and culture, and therefore, I have deep feelings for Japan’s various cultures, customs, and traditions. My roots are in China, but the land that nurtured my growth is ultimately Japan, which can be considered the home that raised me. Thus, I strongly hope that China and Japan can maintain peace and friendship for generations to come.

This requires us to face the history that has occurred, to convey and candidly articulate the sorrow, pain, and even the occasional bursts of anger and hatred of the Chinese people to the Japanese populace, calling for the awakening of Japanese conscience. Being in Japan, I deeply feel that there is still much justice and conscience present in Japanese society. The movement we advocate for, which is about "seeking justice," is by no means simply about the payment of compensation. Rather, it is about ensuring, through this process, that similar tragedies and historical errors will not be repeated.

Naturally, there are various different voices in society, but based on past experience, I will not be afraid. Similarly, I believe there are still quite a few people in Japan who possess courage, conscience, and a sense of justice, even if their numbers are not sufficient. We must summon the courage to speak out and particularly strive to convey the suffering and sorrow endured by the Chinese people during the war to the younger generation in Japan. The 80th Anniversary of the Victory in the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War Commemoration held by China this time gave me immense courage. If misunderstandings exist in Japanese society, we must point out these errors—our hope, and China’s hope, is peace.

As President Xi Jinping has said, the Chinese people have suffered aggression, humiliation, and plunder by foreign powers for over a century. However, the Chinese people did not learn the logic of the jungle from this—the logic that the weak are the prey of the strong—but instead have become more resolute in their determination to uphold peace. This is a declaration that can only be made by a victimized nation, and it points the correct direction for the concept of a Community of Shared Future for Mankind.

I believe the key is to move forward hand-in-hand, with human fraternity as the foundation and trust as the bond. The future may not be bright, and such struggles may persist forever, but we must not fear, we must not give up. We must resolutely express the pain and anger of the Chinese people as victims of war, as well as our legitimate demands toward the Japanese government, and make our voices heard. Enabling Japanese society to reflect on the past and avoid repeating the same mistakes is of paramount importance to the peace of East Asia.

(All images were obtained from publicly available sources.)